By the close of 1861, the Civil War's violent and deadly clashes had reached across the United States. North, South, East, West, as well as down the Gulf Coast, and the central states along the Mississippi River. Battles were occurring all over and increasing in size and frequency.

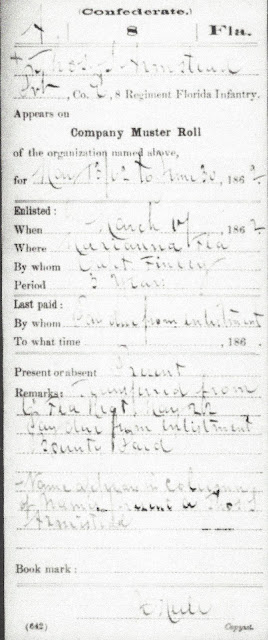

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35637

You may remember from an earlier blog post that the population of the US was growing rapidly and expanding Westward across the continent. In 1860 the population was 31,443,321, spread over 44 states from Maine to Florida, Virginia and North Carolina to Missouri, Arkansas, and Texas, and even to California.

To give you a better picture of how the population was actually located though, let's look at the breakdown between North and South, defined by the two sides in the Civil War. The Northern states (33) had a population of 22,339,989. The Southern states (11) had a population of 9,103,332. That's a big difference in manpower, however, the difference was even greater than that, because out of the total population in the south, 3,521,110 were held as slaves. This leaves a population of about 5.6 million for the south and 22.3 million for the north. Looking at these numbers alone, the end just seems so inevitable. Manpower, railroads, access to goods, manufacturing, were all lopsided in favor of the North. (1)

Still, the people of the South thought they would defeat the North and with the arrival of January 1, 1862, after a year of bloody fighting, their opinion had not changed. But I do think both sides realized the war would not be quick or easy.

There were many battles and skirmishes in 1861. Civil War Saga's website - Civil War Battles (civilwarsaga.com) - lists ten major battles during 1861, including the First Battle of Bull Run/First Battle of Manassas, (4,878 casualties), Wilson's Creek, (2,330), Battle of Dranesville (5,750), and others. This website is an excellent source for information on battles of the Civil War.

The Armistead and Baker families survived 1861, even though they had at least 10 family members enlisted and fighting. This number included William Jordan Armistead, Sr., George Franklin Baltzell, and Simmons Jones Baker, Jr. I did not mention these men in my last blog. They were of the older generation and did not figure prominently in any fighting, but they were listed as members of the Jackson Home Guard from Sep. 1861 to sometime in 1862 when it was disbanded. This was a cavalry group from Marianna and the surrounding area. It was held on standby, as a last resort against the invasion of Union forces. (See Dale Cox's list below).

Jackson Home Guard. https://www.fold3.com/image/120589231Another family enlistment in the Marianna Dragoons was George Albert Baltzell (17). George was the son of George Franklin Baltzell and stepson of Ann Penelope (Armistead) Baltzell. Ann was the eldest of W.J and Eliza's children. There are other family members, cousins, etc., I am sure. I have decided to limit the names a little. (I expect many of you reading this are saying "He should learn how to limit a lot more than that!"). Well, I am afraid that I am not a good editor and so I tend to get too wordy. I am giving you a fair warning, the posts on 1862 will be fairly long and will have a lot of battle information. If you are not into that sort of thing, feel free to skip forward to the parts you are interested in. But I feel it is important to go into some detail to try and give us a better understanding of how bad this terrible war was during this time.

From the website, Civil War Saga, I found information about the battles of 1862. It lists Mill Springs, Jan 19, (814), Fort Henry Feb 6, (119) Fort Donelson, Feb11, (16,537), and Pea Ridge, Mar 6, (6,073) just to name a few in the first months of the year. As a reminder causalities (listed in parenthesis) included: deaths, wounded, and captured. Death counts after a battle were not actually accurate because death caused by the fighting continued for days, weeks, maybe years. The effects of amputations, wounds that didn't heal, gangrene, pneumonia, bullets and shrapnel that could not be removed, etc., caused numerous deaths long after the battle ended.

Battle of Shiloh.

By Thure de Thulstrup - This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID pga.04037.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons: Licensing for more information., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69199332

On April 6-7th, the Battle of Shiloh was fought, resulting in a Union victory. The actual victor of any battle was illusory, however. Casualties were 13,047 for the Union forces and 10,699 for the Confederates and then both armies just moved on to fight again another day. (4) None of the family members I mentioned above were involved at Shiloh (due to enlistments ending and re-enlisting, or not being in a unit sent to that theater of the war).

Lawrence T. Armistead and the 6th Florida, commanded by Colonel Jesse J. Finley, were ordered to report to General E. Kirby Smith at Knoxville. Smith was the Commander of the Department of East Tennessee and participated in the Kentucky Campaign. The 6th, under Finley, was ordered by Kirby to occupy and defend the Cumberland Gap against a possible approach by Northern forces. General Smith meanwhile moved north and won a decisive battle at Richmond, Kentucky. He next marched into Lexington, Ky to hold the line against the approaching Northern forces. After a month-long siege by Colonel Finley and the Confederates against the Federals at Cumberland Gap, the Federals blew up or set fire to their stores of ammunition and arms and escaped to the Ohio River. Colonel Finley and the 6th Florida then reunited with General Kirby at Lexington, Ky. (5)

The Kentucky Campaign.By Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17811337

The Kentucky Campaign ended with "General Bragg, (overall commander of the campaign), either retreating or withdrawing (there is disagreement on which) from Kentucky in front of the Union's General Buel." The South had planned to force the neutral state of Kentucky to get involved on the Confederate side, or to at least recruit a substantial number of soldiers from the state. They were not successful on either count. (6)

Anthony, Thomas, and the 8th Florida Infantry, under command of Colonel R.F. Floyd, were sent to Virginia. Along with the 2nd and 5th Florida, they were ordered to join General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. These regiments were placed in Brigadier General Roger A. Pryor's Brigade, Major General Richard H. Anderson's Division under Major General James Longstreet's command. Henry Hyer Baker's company, Co. A, in the 33rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment, under Brigadier General L. O'Brian Branch's Brigade, in A.P. Hill's Division, and under command of Major General Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson, was also a part of Lee's army. (7)

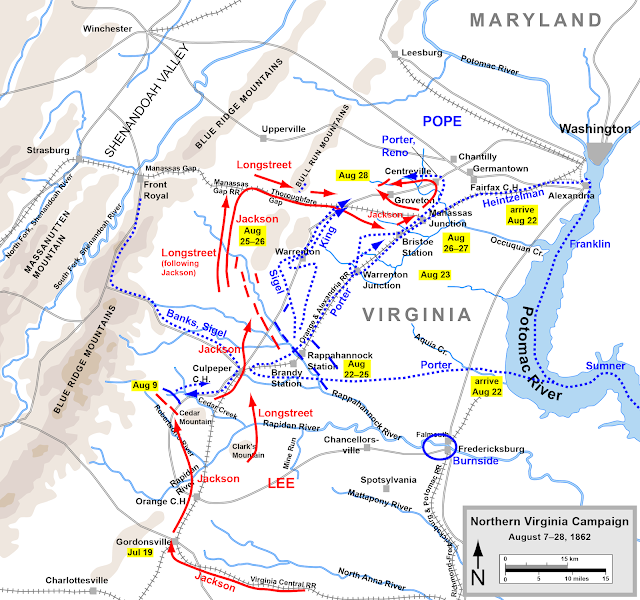

In July, August, and September, General Lee's Army of Northern Virginia executed the Maryland Campaign. In mid-July 1862 they fought a battle near Sharpsburg, Maryland at the opening of the Maryland Campaign. In August Lee found Union General Pope, with a larger force than his, in his way. Lee decided to split his army and have General Longstreet hold the position he had taken right in front of Pope, and have Stonewall Jackson swing around Pope's right flank and destroy Pope's supply lines in his rear. He was not to engage in battle but to burn bridges, destroy railways, etc., and then to meet up with Longstreet in the vicinity of Manassas where Lee would take advantage of whatever opening Pope might give up. (8) See the map below for movements of both armies during August in Northern Virginia.

By Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7100910

By late August, Jackson's troops had marched behind the Bull Run Mountains, through Thoroughfare Gap, and had moved on past Hay Market. Traveling south-southeast from there led him to Gainesville, then across the Warrenton Turnpike, and on to Bristoe Station. At Bristoe Station Jackson's men overwhelmed the few startled guards that were there and set about dismantling train tracks, and causing several trains to wreck. The Broad Run railroad bridge was destroyed next and then it was time to head to Manassas. His troops were weary but Jackson knew he must get to Manassas before Pope could send troops to reinforce the town and most importantly the supply depot there. He left two brigades to guard the Broad Run crossing (at Bristoe Station on the map) in his rear and moved on with the rest of his troops to Manassas. (9)

By ManassasNPS - Manassas Junction3 1862Uploaded by

AlbertHerring, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29594683

Here is how Shelby Foote described it when they arrived at Manassas Station: "The sight that awaited them there was past the imagining of Stonewall's famished tatterdemalions. Acres - a square mile, in fact - of supplies of every description were stacked in overwhelming abundance..." "...warehouses overflowed with rations, quartermaster goods, and ordnance stores." They found everything from molasses, coffee, cigars, jackknives, writing paper, handkerchiefs, whiskey, (but Jackson ordered these barrels destroyed) loaves of light-bread, pickled oysters, canned lobster, and Rhine wine. (10)

As Jackson's men were gorging themselves, Union Brigadier General George W. Taylor and a brigade of four New Jersey regiments were sent down from Alexandria with orders to save the railroad bridge. Instead of stopping at the bridge, they rushed forward to attack the confederate force that was thought to be just a cavalry unit. Little did they know they were running straight into General Lee's largest and probably hardest fighting division in Lee's whole army. The union forces pushed forward under fire, determined to drive this force out. But Jackson unleashed his full force against the oncoming "Jerseymen". "..it was as if they struck a trip-wire. Suddenly demoralized, they turned and scampered, devil-take-the-hindmost." (11)

Jackson burned the railroad bridge and loaded the ambulances and ordnance wagons - all the rolling stock he had - with Federal stores that were most needed, mainly medical supplies. Then once again the men were allowed to recover whatever food, etc. they could. Jackson received word his troops were under attack at Bristoe and realized it was time to fall back to a position of strength and wait for the arrival of Longstreet and the rest of Lee's army. The remaining ammunition dumps were exploded, warehouses and train cars were burned. Then Jackson and his men slipped away. (12)

When General Pope and his men reached Manassas, all they saw was wreckage and desolation. Jackson was nowhere to be seen and they were unsure as to what direction he might have gone. Pope's big fear was that Jackson would be able to escape his grasp and rejoin Longstreet, who he knew would be moving to meet up with Jackson. Pope was not in the dark for long. Late that evening he received two dispatches. One telling him Longstreet was forced back to the west side of Bull Run Mountain and that Jackson had been found in the woods along the Warrenton Turnpike. He had Jackson isolated from Longstreet and, with his greatly overpowering numbers, he could crush Jackson's army, once and for all. (13)

It turns out General Pope had underestimated his adversary. Jackson was not trapped, and he was not trying to escape as Pope thought. After burning the stores at Manassas, Jackson had deliberately headed out for Groveton, located on the Warrenton Turnpike. Jackson, having spent time in the area the year before, knew the lay of the land and the most advantageous place to set up a defensive position. His destination was an excellent covered position where he could wait for Longstreet, or if forced out by Pope, he had a line of retreat that would be reasonably secure. (14)

Jackson stationed his troops in the woods along the Warrenton Turnpike. He was soon notified of Federal forces moving up the pike heading toward Stone Bridge. This was John Gibbons's brigade of four regiments under Pope's command. Waiting for the best moment to strike, Jackson waited until the Union troops were in front of his position, before giving his order to strike. Artillery and infantry emerged from the woods with a deafening roar. The two armies slugged it out for two hours in extremely hard-fought, close-quarter fighting. About 9:00 pm the Federals withdrew across the Warrenton Pike. After conferring, the Union leaders decided to head with their wounded down to Manassas. (15)

Confederate and Union Positions on August 29, 1862.

By Map by Hal Jespersen, www.CWmaps.com, CC BY 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7104342

The next day Jackson positioned his troops behind the high grade of an unfinished railroad, which afforded his men excellent defensive positions to take on any incoming attacks. Jackson poured artillery fire into Pope's men's position located on the other side of the unfinished railroad. Around 10:00 am one of Longstreet's divisions arrived on the scene as Lee's army was beginning to reunite, but all of the units were not yet up. As they arrived, Longstreet's men were deployed straddling the Warrenton Turnpike.

Pope, ignoring Longstreet's arrival, continued focusing on Jackson. He was so intent on crushing Jackson with his superior numbers, he seemed to block out Longstreet's arrival and positioning off of his left flank. Pope promptly sent wave after wave of his troops against Jackson's position behind the berm along the railroad. At times it seemed a portion of Jackson's line would be overwhelmed, but the Federals were repulsed each time. Jackson suffered a large number of casualties but somehow was able to hold the line. (16)

On the map below locate the bottom right panel. This panel shows the early movements of the two armies leading up to this battle. Then move to the upper left panel and you can see in the upper-middle portion the red lines of Jackson's position to the northwest of the railroad line. The final panel in the upper right shows the positioning on Aug 29th and 30th of Jackson, Pope, and Longstreet.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WPMA01_Second_Bull_Run_Campaign.jpg#/media/File:WPMA01_Second_Bull_Run_Campaign.jpg

Once most of Longstreet's forces were up, Lee conferred with Longstreet about attacking Pope's left flank. Longstreet was cautious, waiting for Anderson's Division. This was Thomas and Anthony Armistead's division. They had been left protecting the rearguard so it was the last to come up. He also told Lee he needed to check out the lay of the land and make sure he was aware of the situation before ordering his troops to move. (17)

Anderson finally arrived on the scene with the main body of his army. Lee directed General Longstreet to move into position along Jackson's right flank, which would be just to Pope's left. As mentioned, Pope had inflicted heavy casualties on Jackson and Pope had a much larger force. On Aug 30th, Pope thought the time was right to make an all-out assault on Jackson, overrun his position, and crush him. Again, ignoring Longstreet, the assault on Jackson's position began around 2 pm. This was exactly what Longstreet was hoping would happen. After Pope's attack began, Longstreet smashed into Pope's left flank. With Jackson in front and Longstreet on the left, Pope was smack in the middle of a pincher-like movement by Lee's army that soon crushed Pope's army. Pope's army eventually withdrew to the north across Stone Bridge, blowing it up, after they crossed. (18) This time the withdrawal was not as panicked as the disastrous retreat from the First Battle of Bull Run/First Battle of Manassas had been a year ago, but it was a major defeat for the Union Army nonetheless.

Union Retreat across the Stone Bridge. By Rufus Fairchild Zogbaum - This file is from the

Mechanical Curator collection, a set of over 1 million images scanned from

out-of-copyright books and released to Flickr Commons by the British

Library.View image on FlickrView all images from book View catalog entry for

book., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=60711156

Stone Bridge destroyed by Union troops after retreat.

By George N. Barnard - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16896858

So here, on the plains of Manassas, a year after the first, the Second Battle of Bull Run/Second Battle of Manassas was fought. Pope suffered 13,824 casualties (62% of the total) and Lee 8,353.

As Pope retreated Lee moved his army further into Maryland to continue his Maryland Campaign. His plan was to clear out any Union forces on his way deep into the north, as far as Washington DC if possible. This could be a disruptive and devastating blow to the North. Harper's Ferry was one of those places where he wanted to clear out the Union forces.

Anthony Armistead, Thomas Armistead, and Hyer Baker saw heavy fighting during the battle at Manassas/Bull Run and survived. What would the future hold? Well, they will soon be fighting again, at Harper's Ferry.

References:

(2) National Park Service. U.S., Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007., Original data: National Park Service, Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System, online <http://www.itd.nps.gov/cwss/>, acquired 2007. (3) Source Citation: Historical Data Systems, Inc.; Duxbury, MA 02331; American Civil War Research Database, Source Information: Historical Data Systems, comp. U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009.

Copyright 1997-2009, Historical Data Systems, Inc., PO Box 35, Duxbury, MA 02331.

(5) Historical Data Systems, comp. U.S., American Civil War Regiments, 1861-1866 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1999, Original data: Data compiled by Historical Data Systems of Kingston, MA from the following list of works. Copyright 1997-2000, Historical Data Systems, Inc., PO Box 35, Duxbury, MA 023. (6) Historical Data Systems, comp. U.S., American Civil War Regiments, 1861-1866 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1999, Original data: Data compiled by Historical Data Systems of Kingston, MA from the following list of works. Copyright 1997-2000, Historical Data Systems, Inc., PO Box 35, Duxbury, MA 023. (7) Historical Data Systems, comp. U.S., American Civil War Regiments, 1861-1866 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1999, Original data: Data compiled by Historical Data Systems of Kingston, MA from the following list of works. Copyright 1997-2000, Historical Data Systems, Inc., PO Box 35, Duxbury, MA 023, (8) Foot, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative, Fort Sumter to Perryville, Random House, New York, Copyright 1958. pg 616.

(9) Ibid, pg 617

(10) Ibid, pg 618-619.

(11) Ibid, pg 619.

(12) Ibid, pg 620-621.

(13) Ibid, pg 623

(14) Ibid, pg 624.

(15) Ibid, pg 625-626.

(16) Ibid, pg 631.

(17) Ibid, pg 631.

(18) Ibid, pg 638.