Armistead Family History #26

1863 - Armistead Family in the Civil War (Part Five)

Moving from the death and destruction of 1862 and straight into 1863 the Civil War, a war that both sides believed would last no more than six weeks, begins year three. What will the Armistead family have to face during this year?

In the year 1863, the war would produce more and more bloody battles. Seemingly every battle was more terrible than the last. Casualty counts just continued to escalate as both sides became more adept at killing their enemy and each side dug in for a continued long haul, despite all the tragic losses.

Civil War Saga lists 23 battles in 1863, with a total of 206,488 casualties. In addition to this number, there were numerous other small battles and skirmishes. Two battles during this year will account for the two biggest battles with the highest casualties during the war. (1)

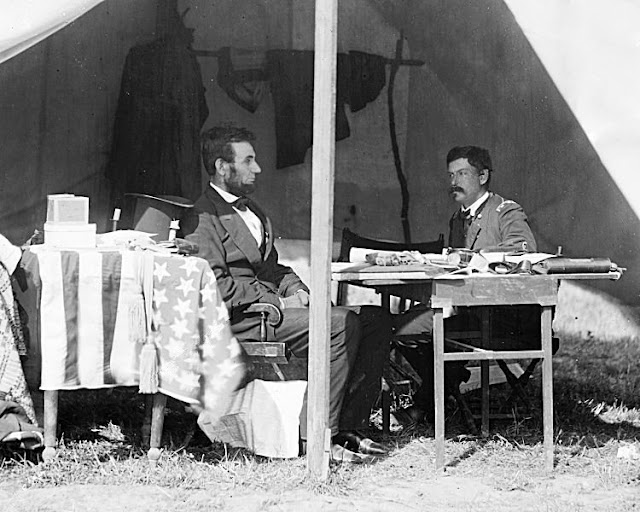

In January 1863 President Lincoln officially published the Emancipation Proclamation that he wrote and presented to his cabinet after the Battle of Antietam. Through this act, he freed the slaves in the seceded states. (2)

In March 1863 President Lincoln, in response to the need for additional soldiers, signed a federal draft act. The Conscription Act of 1863 established the first national draft system and required registration by every male citizen. (3)

At the opening of 1863, Lawrence T. Armistead was serving in Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennesee. While in winter quarters they re-supplied their munitions, food, and men. But as January opened they were quickly on the move again fighting minor battles (as if any battle was really minor) in Tennessee and Kentucky at Murfreesboro, (January) Lexington, (May) Knoxville, (June) Tullahoma, (July). (4)

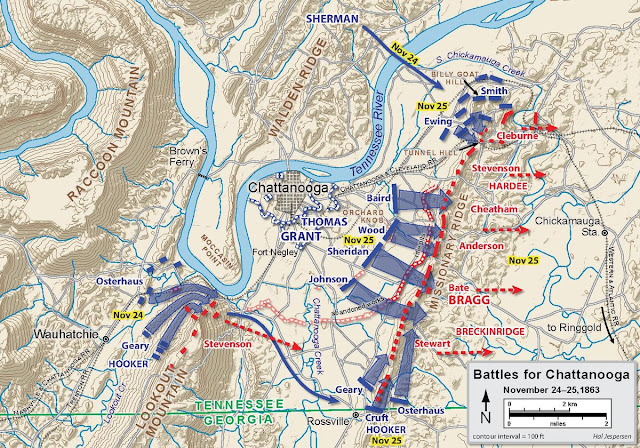

So the last battle I listed above, the Battle of Tullahoma is shown on the map. The fighting occurred between June 24th and July 3rd. The map shows how the battle finally ended up with the Rebels in Chattanooga and the Union army just outside.

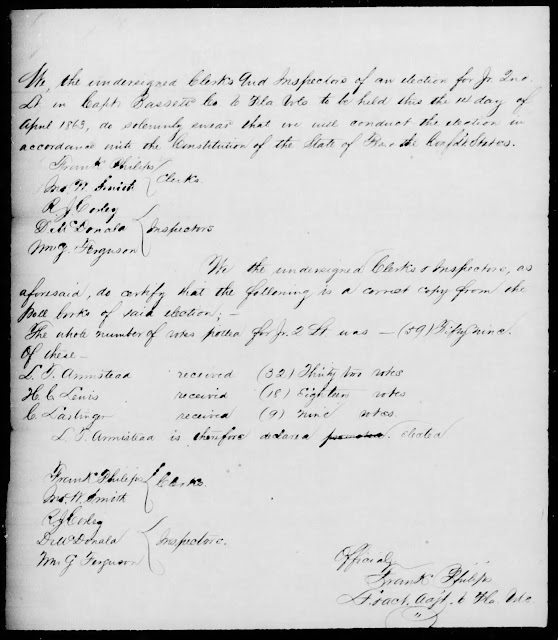

During this campaign from January to July, Sgt. Lawrence T. Armistead on April 14, 1863, was elected by the men in his company to serve as his company's 2nd Lieutenant. (5) I probably don't have to mention the fate of his brother after being elected to the position of Lieutenant. I do find it interesting that these brothers, Lawrence, Anthony, and Thomas, (as well as their first cousin, Henry Hyer Baker) were all elected to serve as leaders for their respective companies. Of course, Lawrence may have had the best preparation for being an officer because he attended West Point not many years before. Lawrence obviously made an impression on these men with his leadership ability. The vote was 32 for Lawrence and 18 and 9 for the other two candidates. You can see the results below.

All the confrontations that ended up with casualties were of course consequential to those involved. However, the 6th Florida Infantry's first really major battle of the year came in September, one year after Anthony lost his life in the Battle of Antietam. The battle was fought along the Chickamauga River and of course, was called the Battle of Chickamauga. Lawrence's future would be greatly changed in this battle.

In September the Army of Tennessee was in control of Chattanooga. The Union forces, just to the north of the city, were led by General William Rosecrans and Major General George H. Thomas. Both sides were keenly aware of the importance of Chatanooga. The city was located on the Tennessee River and was home to the crossroads of four major railroads. It was a vital supply chain link to all of the South. If the North could take control of this area they could severely damage the South's supply lines and contribute to ending the war faster. (6)

By Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9063983

General Rosecrans mounted an assault on the rebels in Chattanooga and was able to force them out of the city and push them southeast into Georgia. General Bragg retreated to the area around the Chickamauga River. Once there, He quickly formulated a plan whereby he would turn the tables and attack the Union Army. Bragg would ask for reinforcements and then counterattack Rosecrans, drive his army back, and recapture Chatanooga. Southern President Davis ordered General Longstreet to join Bragg to beef up his command. General Rosecrans had about 60,000 troops and with the addition of Longstreet's men Bragg's numbers would increase to 65,000 men. (7)

With Rosecrans's army in position to the northwest of the river, General Bragg set in motion his plan to concentrate a counter-attack on one area (his left flank and Rosecrans's right flank) of Rosecrans's army. If he could crush it, and drive it back into the right flank of Rosecrans he could throw that area into confusion and execute his "meat grinder operation." I'll let Shelby Foote explain it better. "Bragg massed his army before nightfall on the east side of Chickamauga Creek, his left at Glass's Mill, a mile above (that is south of) Lee & Gordons, and his right near Reeds's Bridge, five miles downstream... Polk would demonstrate on the left, fixing Crittenden in position, while Buckner and Walker - supported by Hood who was scheduled to arrive in the course of the day - crossed by fords and bridges, well below, with instructions to... 'sweep up the Chickamauga, toward Lee & Gordons's Mill.' As they approached that point, Polk was to force a crossing and assist in driving the outflanked bluecoats towards McLemore's Cove for another try at the "meat grinder" operation. (Hood was) ...charged with executing the gatelike swing that was designed to throw Crittenden into retreat by bringing them down hard on his flank and rear. Meanwhile, opposite Glass's Mill, Hill would hold the pivot and stand ready to strike at any reinforcements from Thomas, moving north from Pond Spring toward the mouth of the cove and packing them back into the grinder. The attack was to open in the far right at Reed's Bridge, and the jump-off hour was set for sunrise." (8)

The ultimate goal was, of course, to drive the Union Army back in panic and confusion so that the Southern Army could drive them from the area and re-take control of Chatanooga.

So just a quick note. I know if you are not interested in Civil War Battles you will struggle to follow Bragg's plans as outlined by Foote. I had to read many times and follow along on the maps to finally make sense of the plan. The map above shows the armies' positions on Sep. 18th and should help understand the plan.

Minor skirmishing occurred in the days leading up to the major battle. The heavy fighting started on Sep 19th. General Bragg hit the left of Rosecrans's position as he had planned. However, heavy fighting all day did not break Rosecrans's line as he had envisioned. You can follow the long day of fighting that took place. Below are the maps for the morning, early afternoon, and late afternoon. The fighting was ferocious with lots of casualties but nothing changed in the two armies' positions. I boiled it down to a short paragraph but in actuality, there was a lot of maneuvering that went on by both armies. I'm not going into a deep analysis of the battle but that does not mean it was not an important battle. It was important and you will see that as we go along.

Lawrence and the 6th Florida were in the reserve corps most of the first day but were thrust into action about mid-afternoon when they were ordered to charge a Federal battery of artillery. Despite being close enough to an enemy battery on its left that it was enfiladed by canister and grapeshot, the regiment carried the position and the battery in front retreated. It was now about sundown and the darkness finally ended the fighting for the day. (9)

In his book, The Chickamauga Campaign: Glory or the Grave, David A. Powell, states this about the first day and night. "In addition to all the formal troop movements planned and executed during those dark hours, the battlefield seethed with other activity. All day long aid parties in both blue and gray had struggled to bring off non-ambulatory wounded and deposit them in the nearest field hospital. That laborious and heartbreaking work was nowhere near finished by the time night settled over the field. The battlefield was still carpeted with thousands of pleading injured-shouting, whispering, or waving for help of any kind. John Glenn of the 27th Illinois, Bradley's Brigade" was on the field. '[W]e remained all night on the ground when we quit fighting, among the dead and wounded for both armies,' he wrote. '...Anyone who has seen a battlefield will never care to see another.' Sergeant Benjamin F Magee of the 72nd Indiana, part of John Wilder's brigade, was not too far from John Glenn that night. The Hoosier listened to the plaintive wail of an unidentified wounded man who pleaded, 'O, for God's sake come and help me!' The repeated pleas rattled a few men who finally decided to try and find the stricken soldier. Picket fire from the Rebels, however, quickly discouraged that idea and the men returned to their lines. The man's cry grew fainter each time it was uttered until it eventually faded away." (10)

On Sep 20th, General Bragg ordered General Longstreet's newly arrived reinforcements into the attack. Now having superior numbers, Bragg tried his original plan once again. On the Union side, General Rosecrans received critical intelligence from his scouts. They reported to him that he had a gap in his lines. Rosecrans moved units of his army around to fill the gap that had been reported to him. Unfortunately, the intel was incorrect. In the process of making moves to fill the gap he actually created a gap. Longstreet recognized this error immediately and quickly exploited the situation. Driving his forces through the gap in Union lines, Longstreet was able to rout a third of the Union forces. With a third of his army in headlong retreat, Rosecrans seemed to be un-nerved right along with his men who were racing north toward Rossville leaving the area to the Confederates. If the rest of the army had followed these panicked troops north the South might have been able to crush Rosecrans's entire army. This would have had far-reaching effects and would have done tremendous harm to the North's cause. (11)

Rosecrans, and his chief aide, James A. Garfield did attempt to stem the flow of the retreating men but without success. They then attempted to find General Thomas at his last known position but were unsuccessful in that as well. Garfield reminded Rosecrans he was the commander and he needed to leave for Chattanooga and he did just that, following his panicked men all the way to Chattanooga. Garfield went in Rosecrans's place to find Thomas. After hours of riding in very dangerous conditions that ended with the death of both his orderlies and serious wounds to himself, Garfield found Thomas at about 4:00 pm. His action, dubbed "Garfields Ride", was seen as a heroic action "that would propel him into the presidency in 1880." (12) Unfortunately for Garfield’s presidency he was assassinated a little over six months after taking office.

Battle of Chickamauga. By Kurz & Allison - Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1484303With the information from Garfield that there would be no reinforcements, Major General George H. Thomas recognized the imminent danger of a complete rout. He took action by taking command of the Union forces left on the field. He began directing the remaining units to consolidate into a defensive potion where they could attempt to hold the surging Rebel forces at bay. They were severely outnumbered but Thomas was able to just barely hold on to his position until dark. The fall of darkness afforded Thomas the cover he needed to organize an orderly retreat from the field, leaving the field to the Confederates. Major General Thomas was described as "standing like a rock" in holding back the Confederate attacks and preventing a complete catastrophe. This quote soon earned him the nickname "The Rock of Chickamauga". In the coming weeks, he would also be rewarded with a promotion. (13)

For Lawrence's part in the days fighting he and the 6th of Florida, and the 54th of Virginia were ordered to support a battalion of Confederate artillery. Shortly, however, they were ordered to their right to reinforce General Patton Anderson and General Kelly. General Anderson gave them their proper alignment and sent them forward. The two regiments eventually cleared the heights of Chickamauga and took about 500 enemy soldiers as prisoners of war. Darkness again ended the fighting on the second day which also turned out to be the end of the battle.

The result of the battle left 8,000 Union soldiers captured along with 51 guns, 23,281 small arms, 2,381 rounds of artillery ammunition and 135,000 rifle cartridges of the Union, and large quantities of wagons, ambulances, and teams, medicines, hospital stores, etc. The human toll was 16,170 Union casualties and 18,454 Confederate. (15)

One of the 36,624 casualties was my great grand-uncle, Lawrence T. Armistead. He was shot or hit by shrapnel in the wrist. He was taken to a hospital in Macon, Georgia where he remained for weeks. I don't know but I am guessing his wrist was shattered. Think about a bullet hitting your wrist. Not much there but bone! Tens of thousands of soldiers that suffered wounds to their limbs ended up with amputations. I have not seen anything that indicated that was the case with Lawrence but from the duration of time he spent in the hospital, I'd say it was very serious. After a long hospital stay, (records show he was hospitalized in November and December) he was furloughed from the hospital on Jan 6, 1864. No mention of a specific length of time for the furlough, the record just said he was furloughed. In examining the records for 1864 there were mentions of him being sick and he was still receiving his lieutenant's pay during the year, but he was not on the active roster as far as I could tell. Don't worry, we have not heard the last of Lt. L.T. Armistead. His story picks up again in September 1864.

The two records above state that Lawrence was wounded and was admitted to the *Ocmulgee Hospital on Oct 4th. Then it shows he was in the hospital during November and December 1863.

The Confederate Army of Tennessee spent a day re-supplying, re-organizing etc. before they set off after Rosecrans. Rosecrans ended up in Chattanooga and Bragg occupied the heights of Missionary Ridge. (See the map above.)

The Battle of Chickamauga was the second bloodiest battle of the Civil War. Gettysburg had the highest number of casualties. (It was fought earlier in the year in July. I will cover that battle in my next post.) It was contested over three days whereas Chickamauga was a two-day battle. (Remember Antietam was the bloodiest single-day battle.)

The Confederate siege of Chatanooga continued until October when General Ulysses S. Grant arrived with reinforcements from his campaign along the Mississippi. Grant was given the command of the Union army in the region. Major General Thomas was promoted to Brigadier General for his efforts at Chickamauga and was given command of the Army of the Cumberland, replacing Rosecrans. In November Grant's forces reversed the loss at Chickamauga by leading a decisive victory over the Confederates in the Battle of Chattanooga on Nov. 23-25. This convincing victory drove the Confederate army from the area and the North gained permanent control of the city with the advantage of controlling supply lines that the South desperately needed. This basically reversed their loss at Chickamauga and turned the entire campaign into a victory for the North. (16)

Next post I'll go back and cover my great-granduncle, Thomas Stewart Armistead, and his first cousin, Henry Hyer Baker during the year 1863 and their participation in the bloodiest battle of the war at Gettysburg.

*The Ocmulgee Hospital in Macon Georgia was one of several locations where wounded soldiers were brought for treatment. Dr. James Mercer Green used his own home for patients, The Floyd House, a converted hotel, was used as well as the Georgia Academy for the Blind. In April 1862 fifteen train carloads of wounded soldiers arrived from the Battle of Shiloh and overwhelmed the city. The citizens rallied to the need for provisions as well as attendants. By the next year when hundreds of wounded soldiers from the Battle of Chickamauga were sent to Macon, the citizens would have to mobilize again. This happened each time a major battle was fought in Georgia. You can read more on the internet about the city's efforts to care for the wounded. Dr. Green's house and historical marker are below.

From HMDB.org website. Tells the story of Dr. Green and the hospitals involved in Macon, GA. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=186792 It's an interesting read. Hop over to the website and take a look. (HMDB stands for Historical Marker Data Base.)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(6).jpg)

%20(13).jpg)

%20(16).jpg)

%20(24).jpg)

%20(25).jpg)