Armistead Family History #25

Battle Aftermath

Read Shelby Foote's words from The Civil War, A Narrative, regarding the immediate aftermath of The Battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg,

"And now in the sunset, here on the right, as previously on the left and along the center, the conflict ended; except that this time it was for good. Twilight came down and the landscape was dotted with burning haystacks, set afire by bursting shells. For a time the cries of wounded men of both armies came from these; they crawled up into the hay for shelter but now, bled too weak to crawl back out again were roasted. Lee's line was intact along the Sharpsburg ridge. McClellan had failed to break it; or, breaking it had failed in all three cases, left and center and right, to supply the extra push that would keep it broken." (1)

With General Lee withdrawing his army and McClellan choosing not to pursue, the Union Army was left to bury the dead and treat the wounded. This was an unusual turn of events because up until now the Union had mostly been the army that had withdrawn from the field first.

As a precaution, I will warn you that these photographs of dead bodies are disturbing to look at. Feel free to quickly scroll through these to other sections of the blog.

Soldiers that died near Dunkard Church prepared for burial.

Buring the dead was a huge undertaking. This massive "three battles in one" confrontation of over 100,000 men produced these staggering numbers: "Nearly 11,000 (10,316) Confederates and more than 12,000 (12,401) Federals had fallen along that ridge and in that valley including a toll on both sides of about 5,000 dead." At the aptly named Bloody Lane alone there were 5,935 casualties. the Union had 3,361 and the Confederates suffered 2,574 at that spot alone. (2)

Anthony Armistead Died at The Battle of Sharpsburg.

I think his brother, Thomas, knew his brother had fallen. They were lieutenants of the same company and most likely were in front leading their men. He may have seen Anthony go down and paused to try to help and seeing there was nothing to do that would help him, or doing what he could to comfort him, continued on the run toward the Sunken Road. If he did not see him go down he would not have known until that night when the officers tried to account for their men that his brother had been a casualty. It is possible that he may have thought his brother had been wounded and captured. Because the Confederates pulled out overnight it seems reasonable that Thomas never saw his older brother again after they took off on the attack at the Bloody Lane and very likely he did not have a chance to tend to Anthony's body or to tell his brother goodbye. I can't stand to think that Anthony might have died in a burning haystack like Shelby Foote referenced above. I don't know how it went down, but Thomas would have known for sure that he was moving out with his company, and his brother was not.

The high number of casualties that resulted from this battle was of major importance. Just think of how difficult it was to bury the dead and treat the wounded. Lee's army had such a high number of casualties it must have been extremely difficult to get all his units reorganized. "'Where is your division?' someone asked (General) Hood at the close of the battle, and Hood replied, 'Dead on the field.' After entering the fight with 854 men, the Texas brigade came out with less than three hundred, and these figures were approximated in other veteran units, particularly in Jackson's command. The troops Lee lost were the best he had--the best he could ever hope to have in the long war that lay ahead, now that his try for an early ending by invasion had been turned back." (4)

As I mentioned above there was a huge number of bodies to bury. Before the soldiers were able to bury the bodies a photographer named Alexander Gardner took photographs of the numerous dead. This was a new phenomenon. "His photographs from Antietam became a sensation, especially as they brought the horrors of the battlefield home to Americans." (5) Photographs had been taken in war before but they were mainly photos of the winning General, etc. This was the first time someone had focused on the dead. Prints were made of the photographs and Matthew Brady had an exhibit in his New York gallery. Hundreds and hundreds of people filed through to see them. The reality of the number of dead soldiers had an enormous impact on people. Before, they had heard the numbers of casualties and that was bad, but now they actually saw the dead, bloated, blackened and disfigured bodies and this was something totally different.

This battle ended Lee's attempt to invade the North, at least for now. The element of a surprise invasion of the North had been lost. His original orders, Special Orders 191, had been found by the Northern army and those plans had been used by the North to thwart Lee's plans. A new plan had to be formulated. This battle undoubtedly changed the trajectory of the war.

The high number of casualties was not confined to the enlisted men. The chain of command for both armies was shattered as well. Many officers were killed and wounded. There were six Generals that died in the battle, three on each side. These men had to be replaced and many of these replacements would be inexperienced compared to the ones they replaced.

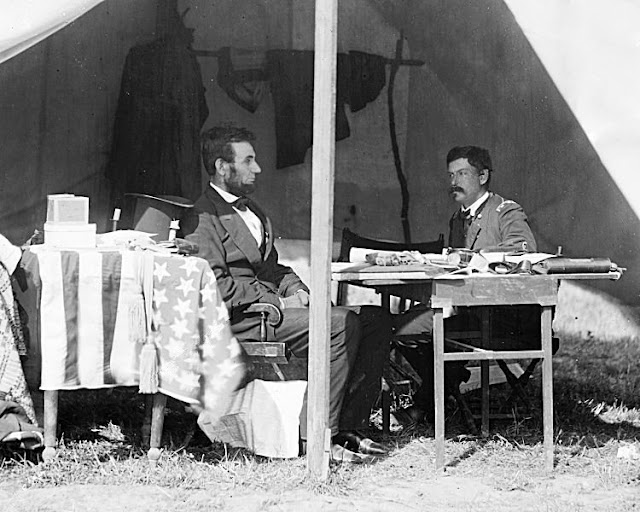

After the battle, President Lincoln was not happy with McClelland. Even though McClelland tried to paint the battle as a great win, Lincoln wasn't having any of that. He knew if McClelland had not hesitated and had forced the issue with Lee, he very well could have crushed Lee's army and shortened the war considerably.

Below is a photo of Lincoln and McClellan meeting in McClellan's tent on October 3, 1862, at Antietam. By Nov. 9, 1862, Lincoln had replaced McClellan as head of the army and promoted Major General Ambrose Burnside to that position. Burnside would not fare any better than McClellan.

Emancipation Proclamation.

After meeting with his cabinet on September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued this preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The third paragraph reads:

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom. (6)

Lincoln knew the proclamation itself would not do anything to change the South's mind, in fact, might cause even more hatred in the South. He hoped it would at least help to unify his party and to some extent the North. It would end up having a far greater impact than he thought.

Politicians and newspapers weighed in on the subject, some saying it helped, others saying it hurt, and some didn't think it did anything. But most citizens of the North did not study the proclamation in detail. The fact that an emancipation order had been made took on a different meaning for the general public of the North. As it turned out for most of the people of the North "the container was greater than the thing contained, and Lincoln became at once what he would remain for them, 'the man who freed the slaves.'" (7) In addition the people of England and France, because of this declaration, now saw the war as a war to free the slaves. This put so much pressure on the leaders of those two countries that the possibility that either country would enter the war on the side of the South was effectively ended. (8)

Interesting Side Note.

As I was researching the Battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg, I discovered there were two other Armisteads in the battle. One was named Alexander Armistead. He was a First Seargent, Co. A, 32 Regiment, Virginia Infantry. He was wounded and taken prisoner by the Union Army. He was taken to a hospital but he would later die from his wounds while in custody at Frederick City, Maryland. (9) The exact date is not listed but it was within the next couple of months or less. My tree in Ancestry says we are 5th cousins, 3 times removed. That is not a fully documented connection but should be close. It appears our most recent common ancestor would be the immigrant William Armistead, so I believe we are distant cousins but I'm not sure about those numbers.

The second Armistead was Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead. Upon arriving on the field of battle on the 17th, Armistead's Brigade (Commanded by Lewis Armistead.) which served under Major General R H Anderson's Division, rather than being ordered into the battle at the Bloody Lane with Anderson's division, was ordered to serve as defensive support behind General McLaw's Division near the Dunker Church. He was not happy with this assignment so he purposefully stood out in front of his men and waited impatiently to be ordered to the attack. Oddly enough, while standing there in front of his men, an enemy cannonball rolled over a hill and struck Armistead in the ankle. He was not severely injured but was injured enough that he could not continue his command and was compelled to leave the field. (10) Most of you may already recognize this name. He is well known for his action at the Battle of Gettysburg which was still to be fought in July of 1863. Lewis A. Armistead is something like a 5th cousin, 4 times removed. (Again, I'm not guaranteeing those numbers.) I'll have more on Lewis in a later post.

In an effort to take less than a year between blog posts, I have not done further research on other relatives in this battle. But I think there is a very good chance there are others that are distant cousins.

Paperwork Regarding Anthony Armistead's Death.

Below I have included several pages from Fold3.com showing the military records relevant to Anthony's death and the filing of a claim by his father, William J. Armistead for Anthony's back pay. He appointed his son, Thomas Stewart Armistead, as his power of attorney. There are about 30 documents in Fold3 regarding Anthony. The document showing the issuance of the payment of $205.33 to Thomas Stewart Armistead, was dated almost a year after Anthony's death. So you can see there was bureaucracy even back then. I can only imagine how difficult this was for William Jordan and Mary Eliza Armistead. I am sure they felt like their world had collapsed around them. Death of another child, three other sons still out there fighting, most likely their farm was failing and they were having difficulty finding a way to support all the people it took to run their plantation. And, there was no end in sight for this horrible war.

Military Records for Anthony Armistead

Source Citation: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, D.C.; Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Florida; Series Number: M251; Roll: 81Source Information: Ancestry.com. U.S., Confederate Soldiers Compiled Service Records, 1861-1865 [database online]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. U.S., Confederate Soldiers Compiled Service Records, 1861-1865 provided by Fold3 © Copyright 2011 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved. All use is subject to the limited use license and other terms and conditions applicable to this site. Original data: Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers. The National Archives at Washington, D.C.

Battle of Fredricksburg.

Lewis Armistead, Thomas Armistead, and Henry Baker escaped the carnage at Sharpsburg, but before the year was over they would have another big battle to fight, this time at Fredericksburg. President Lincoln had removed McClellan and appointed General Burnside to head the Union Army. Burnside planned to turn the tables on General Lee and make a quick crossing of the Rappahannock River at Fredricksburg and, after a fast march, make an attack on the Confederate Capitol of Richmond, VA. He believed the surprise move would allow him to attack Richmond before Lee could get there to defend it.

Burnside requested pontoon bridges to be brought up to the river so he could get his men across. Things got bogged down in bureaucracy (there's that word again) and he did not get the pontoon bridges in time to beat Lee across the river. Burnside finally crossed the river on Dec 13th and decided to attack Lee even though Lee's men had set up very strong defensive positions in and around Fredricksburg. The result was a slaughter of Burnsides's troops as he sent them against Lee's entrenchments time after time, suffering heavy losses as they were repelled each time. The Battle of Fredricksburg had 17,929 casualties, 13,353 Union, and 4,576 Confederate. Union losses were three times those of the Confederates. (11)

This huge win by Lee's army took some of the sting out of his loss at Sharpsburg and helped him regain some momentum.

The Civil War Saga website lists 43 battles in 1862. Thomas S. Armistead would not fight a major battle again until the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May 1863. (11)

References:

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(6).jpg)

%20(13).jpg)

%20(16).jpg)

%20(24).jpg)

%20(25).jpg)